I am sure if you are reading this blog post, you have come across an ArrayBlockingQueue or some other form of queue. In general, queues serve as a way to pass data or work between threads in concurrent systems. ArrayBlockingQueue is really a great choice in many cases because it provides a bounded, thread-safe queue that ensures memory usage is controlled and that producers and consumers are properly coordinated, unlike unbounded queues, which can grow without limits and cause serious memory issues under heavy load.

However, as its name suggests, ArrayBlockingQueue is blocking. It achieves this by using locks internally. In high-performance systems like logging pipelines, high-frequency trading engines, event processing systems, or real-time message handling, where every millisecond or even nanosecond is important, this blocking behavior actually matters. You want to design a queue that avoids unnecessary blocking and coordination overhead between threads, which greatly affects throughput.

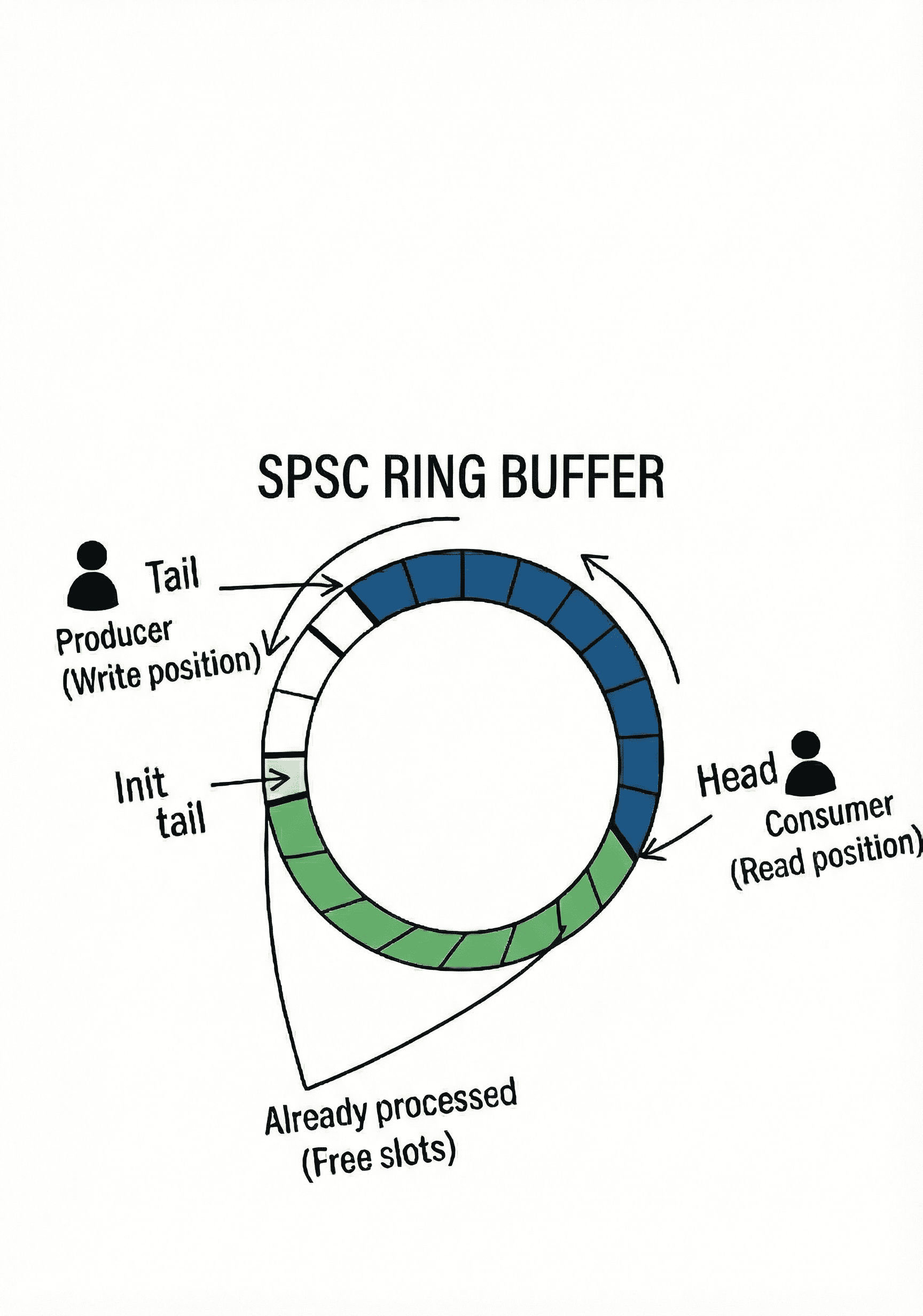

This is exactly what a ring buffer is. A ring buffer is a circular, bounded data structure that is non-blocking. It is designed to provide very high throughput by allowing data to move from producer to consumer with minimal synchronization.

In this blog post, we look at the internals of ArrayBlockingQueue and a ring buffer, and through benchmarks, confirm why a ring buffer beats ArrayBlockingQueue, and why you should consider using one in performance-critical systems.

The Bottleneck: Inside an ArrayBlockingQueue

ArrayBlockingQueue was not designed around raw throughput. It focuses on safety and general-purpose use. General-purpose solutions are usually not what you want to go for when high throughput is a strict requirement.

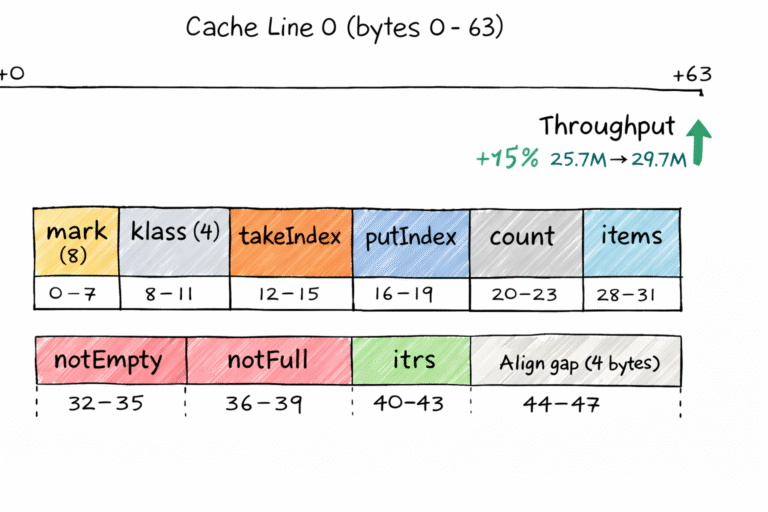

At its core, ArrayBlockingQueue is backed by a fixed-size array. Elements are inserted and removed using two indexes, putIndex and takeIndex, that advance in a circular manner. On the surface, this already looks similar to a ring buffer, but the similarity ends there.

It uses a single ReentrantLock to guard access to the underlying array, so both producers and consumers calling put or take must acquire the lock before they can proceed. In cases where the lock cannot be acquired, threads are forced to park and wait.

If the queue is full, producer threads are blocked. If the queue is empty, consumer threads are blocked. This design ensures thread safety, fairness, and correctness.

However, every operation on the queue goes through the same synchronization point. Even in the simple case of a single-producer, single-consumer workflow, which we will focus on in this blog post, threads still contend for this lock. As the workload increases, the cost of this contention becomes obvious and throughput drops. Locking, unlocking, and thread signaling all have a cost, and because of this, ArrayBlockingQueue becomes limited in high-throughput scenarios.

The Solution: The Lock-Free Ring Buffer

A ring buffer is designed to be bounded, just like an ArrayBlockingQueue. It also uses indexes that move forward in a circular manner as elements are written and read. However, it completely eliminates the need for locks to protect access to the array in the case of a Single-Producer, Single-Consumer (SPSC) setup. Variants like SPMC or MPSC can also be lock-free, but they usually rely on atomic operations rather than simple volatile variables.

In an SPSC ring buffer, the producer is the only thread that ever writes to the buffer and advances the tail index. The consumer is the only thread that ever reads from the buffer and advances the head index. Because each index is modified by only one thread, there is no contention and no need for locking.

To ensure that when the producer writes data, the consumer sees it in the correct order, memory visibility guarantees are used. This is typically implemented using memory barriers, most commonly through volatile fields or VarHandle acquire and release semantics. There is no blocking and no thread parking involved.

This alone is already a very big win in high-workload scenarios.

However, there are additional mechanisms that a typical ring buffer implementation uses to further improve performance. One of these is the way indexes are laid out in memory to avoid the effects of false sharing. This is usually done through padding, which ensures that the head and tail indexes do not share the same CPU cache line.

Another important optimization is how index wrapping is handled. Instead of using the modulo operator (%) to wrap indexes, a ring buffer uses bitwise operations. To make this possible, the buffer capacity must be a power of two. Wrapping is then done using a bitwise AND operation. This is significantly cheaper than modulo, which involves division and is relatively expensive at the CPU level. While this may seem like a small detail, the impact becomes very noticeable when these operations run millions of times per second in a tight loop.

This is a very simple implemtation of a SPSC Ring Buffer

public final class SpscRingBuffer<E> {

private static final VarHandle HEAD;

private static final VarHandle TAIL;

static {

try {

MethodHandles.Lookup l = MethodHandles.lookup();

HEAD = l.findVarHandle(SpscRingBuffer.class, "head", long.class);

TAIL = l.findVarHandle(SpscRingBuffer.class, "tail", long.class);

} catch (Exception e) {

throw new ExceptionInInitializerError(e);

}

}

@SuppressWarnings("unused")

private long p1, p2, p3, p4, p5, p6, p7;

private volatile long head; // consumer-owned

@SuppressWarnings("unused")

private long p8, p9, p10, p11, p12, p13, p14;

private volatile long tail; // producer-owned

@SuppressWarnings("unused")

private long p15, p16, p17, p18, p19, p20, p21;

private final Object[] buffer;

private final int mask;

public SpscRingBuffer(int capacity) {

if (Integer.bitCount(capacity) != 1) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Capacity must be a power of two");

}

buffer = new Object[capacity];

mask = capacity - 1;

}

// Producer only

public boolean offer(E item) {

long currentTail = (long) TAIL.getOpaque(this);

long nextTail = currentTail + 1;

long currentHead = (long) HEAD.getAcquire(this);

if (nextTail - currentHead > buffer.length) {

return false;

}

buffer[(int) (currentTail & mask)] = item;

TAIL.setRelease(this, nextTail);

return true;

}

// Consumer only

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

public E poll() {

long currentHead = (long) HEAD.getOpaque(this);

long currentTail = (long) TAIL.getAcquire(this);

if (currentHead == currentTail) {

return null;

}

int index = (int) (currentHead & mask);

Object item = buffer[index];

buffer[index] = null;

HEAD.setRelease(this, currentHead + 1);

return (E) item;

}

}Benchmark

We now run a simple benchmark to compare the throughput of our custom ring buffer with that of ArrayBlockingQueue

@BenchmarkMode(Mode.Throughput)

@OutputTimeUnit(TimeUnit.SECONDS)

@Warmup(iterations = 3, time = 2)

@Measurement(iterations = 4, time = 2)

@Fork(3)

@State(Scope.Group)

public class SpscQueueBenchmark {

@Param({"1024", "65536"})

int capacity;

private static final Integer ITEM = 1;

ArrayBlockingQueue<Integer> abq;

SpscRingBuffer<Integer> ring;

@Setup(Level.Trial)

public void setup() {

// Pre-allocate to ensure fresh heap layout per fork

abq = new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(capacity);

ring = new SpscRingBuffer<>(capacity);

}

// -------- ArrayBlockingQueue (Baseline) --------

@Benchmark

@Group("abq")

@GroupThreads()

public void abqProducer() throws InterruptedException {

abq.put(ITEM);

}

@Benchmark

@Group("abq")

@GroupThreads()

public void abqConsumer(Blackhole bh) throws InterruptedException {

bh.consume(abq.take());

}

// -------- Ring Buffer (High Performance) --------

@Benchmark

@Group("ring")

@GroupThreads()

public void ringProducer() {

while (!ring.offer(ITEM)) {

Thread.onSpinWait();

}

}

@Benchmark

@Group("ring")

@GroupThreads()

public void ringConsumer(Blackhole bh) {

Integer v;

while ((v = ring.poll()) == null) {

Thread.onSpinWait();

}

bh.consume(v);

}

}Run mvn clean install to build the project, then run the benchmark with:

java -jar target/benchmarks.jar

Results

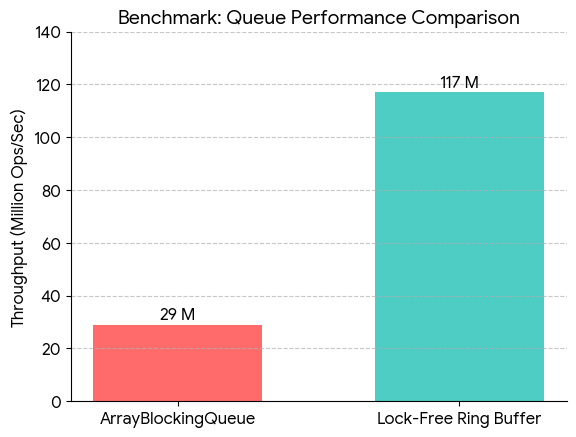

In our benchmarks, the lock-free ring buffer achieved roughly 117 million operations per second, while ArrayBlockingQueue reached about 29 million operations per second. This represents an approximate 4× increase in throughput.

Conclusion

The benchmark results speak for themselves. In a simple SPSC setup, the ring buffer moves data several times faster than ArrayBlockingQueue because it avoids locks, thread parking, and unnecessary coordination. ArrayBlockingQueue is still a solid, general-purpose queue, but that generality comes at a cost. When throughput matters and the concurrency model is known, a ring buffer is simply the more appropriate tool. This approach is not new or experimental. It is already used in well-established systems such as LMAX Disruptor, JCTools, and Aeron, which apply the same lock-free, CPU-aware design principles.