Getters and Setters. I believe you have auto-generated these before. It is a very common behavior when writing code to just directly generate getters and setters. I mean, our IDEs help us do this effortlessly, and for a long time, many frameworks seemed to expect them.

This habit just feels like the natural thing to do: create a class with its fields private and then generate getters and setters. We often justify this by calling it encapsulation, arguing that since the fields are private, the object is safe. But this is a misunderstanding of what encapsulation actually means. If you have a class with a private field status and then a public method setStatus(Status s) that directly sets the value, how is that really encapsulation?

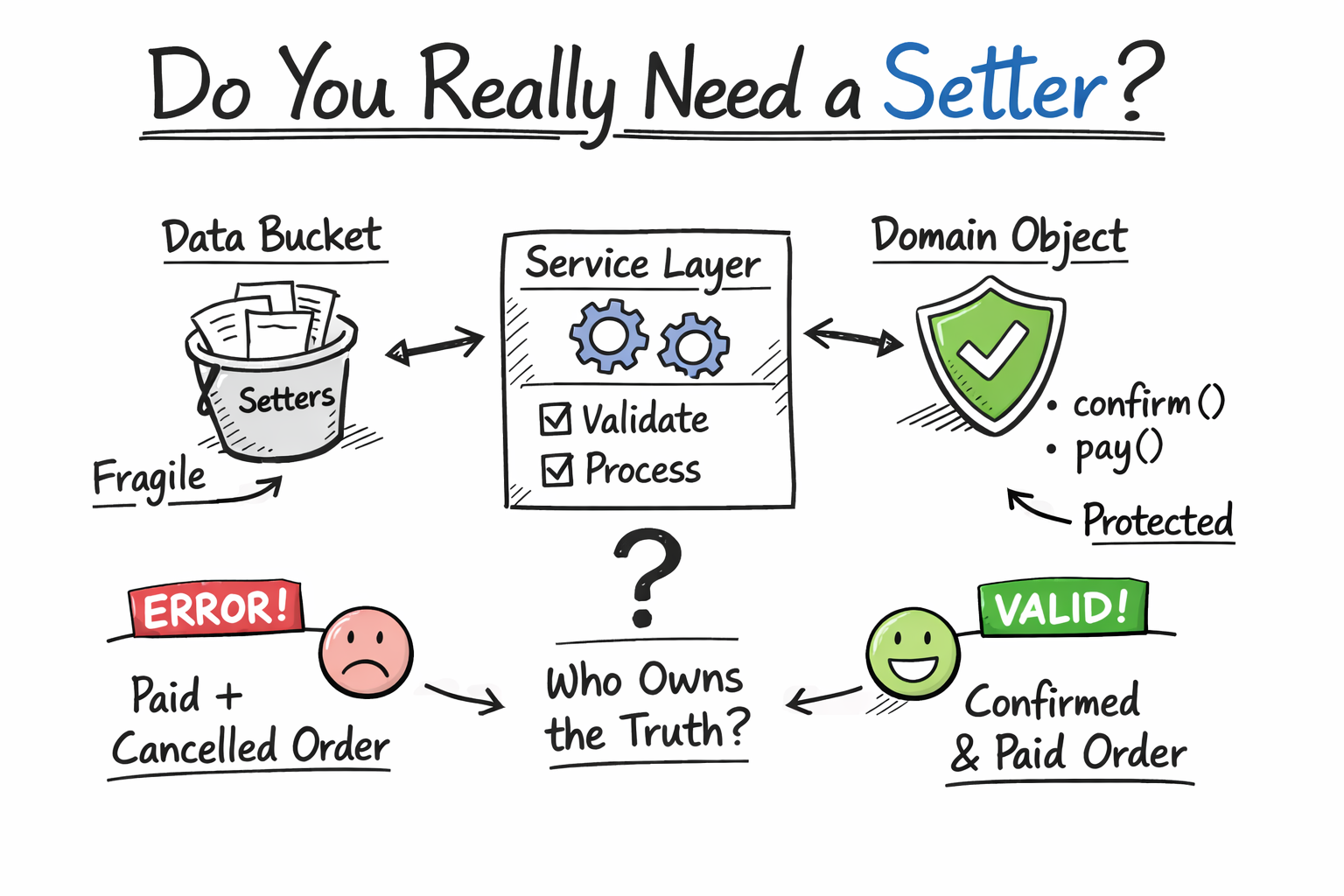

For decades, we have applied this pattern to systems with increasingly complex business rules. The result? Domain correctness is delegated to service layers, validation logic is duplicated, and we are left with “Anemic” domain models that are incapable of protecting themselves.

In this blog post, we will explore why this habit persists and how to fix it.

Domain Objects Are Not Data Buckets

There is a core misconception between data representation and domain modeling.

A domain object is not just some database row loaded into memory. It represents a business concept that is already meaningful and already valid. If an Order exists in the system, the rest of the code should be able to rely on the fact that it obeys the rules that define what an order is.

Let us illustrate this. Consider a simple, setter-based design:

class Order {

private OrderStatus status;

private boolean paid;

public void setStatus(OrderStatus status) {

this.status = status;

}

public void setPaid(boolean paid) {

this.paid = paid;

}

}This looks like a normal Java POJO; nothing looks obviously wrong. However, the problem arises if this is actually a domain object. What if we introduce a business rule stating that an order must be confirmed before it can be paid?

In this design, the object cannot enforce that rule. The responsibility is pushed outward, typically into a service:

if (order.getStatus() != CONFIRMED) {

throw new IllegalStateException("Cannot pay unconfirmed order");

}

order.setPaid(true);At this point, the Order no longer defines its own validity. It relies on callers to remember the rule and apply it correctly, everywhere, forever.

Any code path that forgets this check, be it a batch job, a migration, or a new feature, can corrupt the system. This is exactly what we call an Anemic Domain Model.

Why “Put Logic in Services” Sounds Reasonable and Why It Fails

It is very common to justify the approach of having public setters in entities (or your domain) with the principle of separation of concerns. The argument is that the domain is just a model, and services are the right place to handle logic. Since services already manage workflows, transactions, and coordination, putting validation there feels natural.

The problem is not that services perform validation or contain logic. The issue is the kind of logic they perform.

Validation in service classes normally happens before mutation. This makes it conditional. It depends on control flow and developer discipline. Domain validation that happens inside the object ensures the entity is never in an invalid state. This is structural. It cannot be bypassed.

When rules that affect the correctness of state live only in services, we can only hope for them to be respected. Nothing stops a developer from ignoring them. When rules live in domain objects, correctness becomes something the system enforces automatically.

From Setting State to Expressing Behavior

The solution is not to move validation into the setter (which often throws exceptions at inconvenient times) but to stop the “setting by default reflex” altogether. We need to move from Data Manipulation to State Transitions.

In a robust domain model, you do not change values; you perform actions.

Instead of exposing setStatus, the object exposes behavior:

public void confirm() {

if (this.status != OrderStatus.PENDING) {

throw new IllegalStateException("Order cannot be confirmed.");

}

this.status = OrderStatus.CONFIRMED;

}

public void pay() {

if (this.status != OrderStatus.CONFIRMED) {

throw new IllegalStateException("Only confirmed orders can be paid.");

}

this.paid = true;

}Now the rule is inseparable from the state it protects. No caller can pay an unconfirmed order, not because they remembered to validate, but because the model makes the invalid state impossible to represent.

This does not turn the domain into a service. The object is not orchestrating workflows or talking to external systems. It is simply refusing to become invalid.

When Mutation Is Needed: The Wither Pattern

Sometimes you need to update a value while preserving immutability, such as correcting a shipping address.

In these cases, the solution is not a setter but a wither: a method that returns a new, validated instance.

public Order withShippingAddress(Address newAddress) {

if (this.status == OrderStatus.SHIPPED) {

throw new IllegalStateException("Cannot change address after shipping.");

}

return new Order(this.id, this.items, newAddress, this.status);

}The original object remains valid and unchanged. The new object reflects the update. You gain flexibility without sacrificing correctness or thread safety.

DTOs, Records, and Framework Myths

I am sure there is still the objection: “But I need setters for DTOs.”

This is where roles matter. A DTO is not a domain object. It is a transport structure, often representing incomplete or untrusted data. It has no invariants to protect.

Modern Java already gives us the right tool for this: records.

Records are immutable, concise, and explicit. They eliminate boilerplate without pretending to be domain models.

And contrary to persistent belief, frameworks do not require setters on domain objects:

- JPA can use field access and constructors.

- Jackson supports constructor binding and

@JsonCreator.

We might have been weakening our models to satisfy constraints that no longer exist.

Conclusion: Who Owns the Truth?

This post is not arguing that setters should never be used. There are situations where they are reasonable, and in some cases you may even be obliged to use them because of framework or integration constraints. The point is not to ban setters, but to pause before adding them by default.

In real systems, a domain object does not need to own every business rule, but it must own its invariants. These are the internal rules that ensure the object never contradicts itself. You should not be able to have an order that is simultaneously “Paid” and “Cancelled,” just as a shipped order should not be able to change its address. If a public setter allows those states to exist, the object has already lost its integrity.

Services still play an essential role. They handle workflows and policies: when something happens, which steps are involved, and what external checks are required. Once a service reaches a decision, however, it should tell the domain what to do not manually adjust its internals.

The separation is simple. Services manage the process. Domain objects protect their validity.

When objects are reduced to data buckets with setters, services are forced to micromanage state, and validation logic spreads everywhere. Replacing setters with behavior methods or controlled state changes keeps that responsibility where it belongs.

So the next time your IDE offers to generate setters, pause for a moment. Ask whether you are modeling an object that can protect itself, or one that depends on everyone else to behave correctly. That pause is where design actually starts.