Java provides us with very strong concurrency tools, and they are very convenient to use. In most applications, when we want concurrency, we simply stick to the defaults provided by the JDK and we can run multiple tasks concurrently.

Now, If your application is handling very stable and predictable workloads, this can be absolutely fine. For example, in production with small traffic and no serious spikes in workload.

We often see codes like these:

When you want to run a task asynchronously: CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> callRemote());

Or sometimes we define a fixed thread pool so we can control how many threads run work at the same time: var exec = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(32);

Or even the popular parallel stream when we want to process a collection in parallel: items.parallelStream().map(this::work).toList()

Now the question is: what is happening behind the scenes?

Every single one of these has a specific way it handles the workload you assign to it. And at the core, this is all about managing multiple tasks and distributing them across the threads that are actually available.

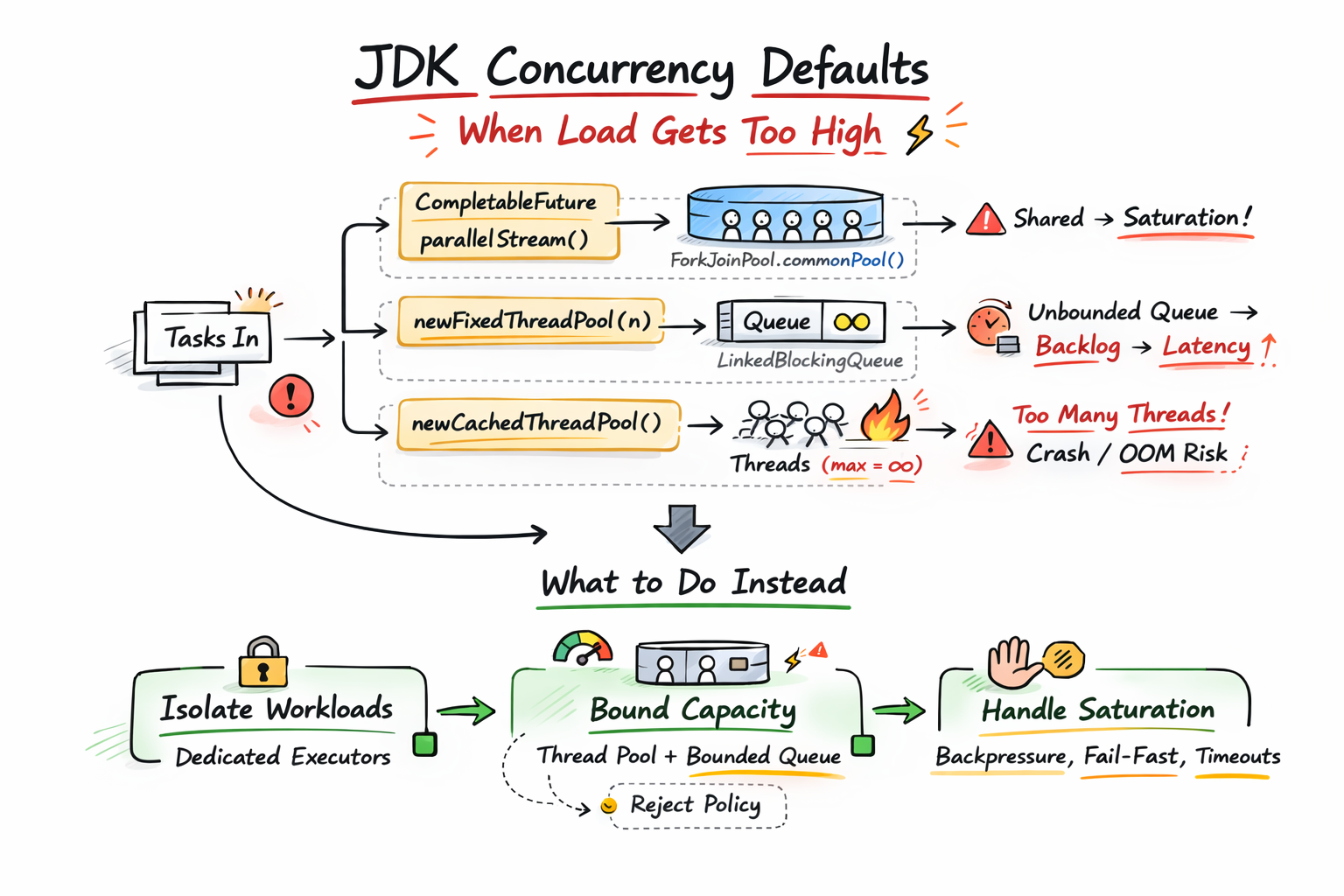

So how do these defaults behave when there’s heavy workload or sudden spike?

That is what we are going to discuss in this post.

We will break down the hidden behaviors of these “default” concurrency utilities, and the key things you must consider before using them in code that can see real production pressure.

The Capacity Saturation Question

Every system is limited, and resources like CPU, memory, and threads are not infinitely available. So what happens when your incoming requests exceed your available capacity?

Whatever concurrency choice you made, your system must answer that question. When more tasks arrive and the available threads are already busy, it has only a few options: it can create more threads, it can queue the tasks somewhere, or it can reject work and push back.

Now let’s see the exact behavior of the JDK defaults we mentioned.

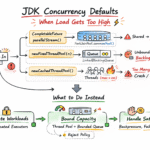

Exposing the Default Overload Behaviors

CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(…)

Now, this is a very common production code :

CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> callRemote());

If you don’t pass an Executor, the JDK picks one for you. And the default is the common ForkJoin pool: ForkJoinPool.commonPool(). This means you are not creating a private pool for this work. You are submitting to a pool that is shared across the entire JVM process. And other things can use it too, including other CompletableFuture calls and, typically, parallel stream work.

Now, if your async work is CPU-bound and short, the common pool can be fine. But most times, callRemote() is not CPU work. It blocks. It waits on network, disk, database, locks, or timeouts.

So what happens when you have many tasks coming in and the common pool threads are already busy? The incoming tasks are forced to wait in the pool’s internal queues.

Also, because ForkJoinPool.commonPool() is a static resource shared across the entire JVM, pool saturation/starvation” in one section of your code can directly affect unrelated sections of your application. For example, if one feature submits slow blocking database calls and saturates the pool, a completely unrelated feature trying to process a list with parallelStream() is forced to wait in the exact same queue.

Also note: this is not limited to supplyAsync(). runAsync() behaves the same way when you don’t pass an executor.

How to Fix this:

If the work can block, stop using the implicit executor and pass your own:

ExecutorService ioPool = new ThreadPoolExecutor(

32, 32,

30, TimeUnit.SECONDS,

new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(10_000),

new ThreadPoolExecutor.CallerRunsPolicy()

);

CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(this::callRemote, ioPool);

// same idea for runAsync(...)

Here we have isolated this blocking task to its own dedicated pool of 32 threads with a strict 10,000-item queue to prevent resource starvation. If that queue reaches capacity, the system forces the submitting thread to execute the task itself, providing an automatic backpressure mechanism until the pool has available slots.

Executors.newFixedThreadPool(n)

This is also very common code that feels safe because it provides a thread pool cap:

var exec = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(32);

But here is the issue. A fixed thread pool is literally “a fixed number of threads operating off a shared unbounded queue.” Internally it is a ThreadPoolExecutor backed by a LinkedBlockingQueue and if you do not provide a capacity, that queue’s default capacity is Integer.MAX_VALUE.

This means that, when all the 32 threads are busy, new tasks do not get rejected, they get queued.

So under load, latency increases because tasks spend more time waiting before they even start and also memory usage increases, since every queued task is still a Java object sitting in the heap.

How to Fix this:

If you want a fixed pool, make the queue bounded and decide what happens at saturation:

ExecutorService exec = new ThreadPoolExecutor(

32, 32,

30, TimeUnit.SECONDS,

new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(5_000),

new ThreadPoolExecutor.CallerRunsPolicy() // or AbortPolicy() for fail-fast

);

By bounding the queue, you create a hard resource limit that prevents the backlog from growing infinitely. Once that limit is reached, your choice of rejection policy explicitly decides how to handle the saturation: either forcing the producer thread to handle the task or rejecting it.

Executors.newCachedThreadPool()

This one is also very common because it feels “smart”. It grows when needed and shrinks when idle.

var exec = Executors.newCachedThreadPool();

But under the hood, the JDK builds it as a ThreadPoolExecutor with:

corePoolSize = 0maximumPoolSize = Integer.MAX_VALUEkeepAliveTime = 60 secondsworkQueue = new SynchronousQueue<>()

Now, the SynchronousQueue has zero capacity. It doesn’t hold tasks. It is mainly a direct handoff. A task is only accepted if a worker is ready to take it immediately.

So when threads are busy and a new task comes in, there’s no queueing. The executor has to create a new worker thread to handle the task, and it will keep doing that up to Integer.MAX_VALUE.

So the overload behavior here is: create more threads and this is highly dangerous when the work blocks. In production, this default causes the JVM to create too many threads and forces the OS to spend more time context switching. You can also end up with an OutOfMemoryError because the system cannot handle the memory required for thousands of thread stacks.

How to Fix this:

ExecutorService exec = new ThreadPoolExecutor(

0, 64, // Hard cap based on system limits

60L, TimeUnit.SECONDS,

new SynchronousQueue<>(),

new ThreadPoolExecutor.CallerRunsPolicy() // Backpressure when saturated

);

Now the behavior is no longer infinite thread creation for every task when idle threads are unavailable. Instead, we grow them to a defined limit based on system resources and provide explicit saturation handling through a rejection policy.

parallelStream()

This is also very common code when we want to process a collection in parallel:

items.parallelStream().map(this::work).toList();

Parallel streams, just like CompletableFuture, typically use the same shared fork-join pool by default (ForkJoinPool.commonPool())

So it exposes the same issue we discussed earlier: if work() is blocking (DB, network, locks, timeouts), you can saturate the common pool and spill latency into unrelated parts of the application.

How to Fix this:

- If

work()can block: don’t useparallelStream()for it. Use an executor you control (same idea assupplyAsync(..., executor)). - If you still want parallel stream semantics but with controlled parallelism, run it inside a dedicated fork-join pool:

ForkJoinPool pool = new ForkJoinPool(8);

try {

var result = pool.submit(() ->

items.parallelStream().map(this::work).toList()

).join();

} finally {

pool.shutdown();

}

Also note: it is possible to tune the common pool parallelism globally, but that affects the entire JVM, not just one stream.

Conclusion

In this post, we have shown that JDK concurrency defaults come with a default overload behavior. That is what happens when the number of tasks coming in is higher than what your system can execute at that moment, because threads are already busy and the work is not being drained fast enough.

It’s important to note that defaults are fine when workloads are stable and predictable, but when your workload is unpredictable, or blocking heavy, you shouldn’t rely on default behavior. You have to make an explicit choice to isolate workloads, bound capacity, and decide what happens at saturation.

Also, choosing thread count is a whole blog post on its own. If you want a solid starting point, the Zalando post is a good reference here: How to set an ideal thread pool size

In real systems, you often combine strategies (bounded pools, backpressure, fail-fast, call-site limits, etc.) to get predictable behavior under pressure.