If you’re reading this blog post, I’m sure you’ve come across the concept of ACID in databases. Database operations happen in transactions, which act as a single unit ensuring that everything succeeds completely or fails entirely with no partial effects.

This ensures that the database moves from one valid state to the next, and concurrent transactions don’t interfere with each other. They run as if they were sequential, using concepts like locking or versioning to prevent issues such as dirty reads or lost updates. This allows multiple database transactions to run simultaneously without corrupting data.

Software Transactional Memory (STM), originally proposed by Nir Shavit and Dan Touitou in their 1995 paper “Software Transactional Memory,” borrows this same principle but applies it not to persistent storage but to RAM. That is, to shared data in memory. The implications are massive. You won’t have to bother about deadlocks, livelocks, race conditions, or complex locking mechanisms. You can write code on multicore systems as if it was single-threaded. Just wrap your operations in an atomic block, and let the system handle the conflicts and retries for you

In this blog post, we will explain how STM works, a practical use case, and some of the drawbacks you need to be aware of.

How STM Actually Works

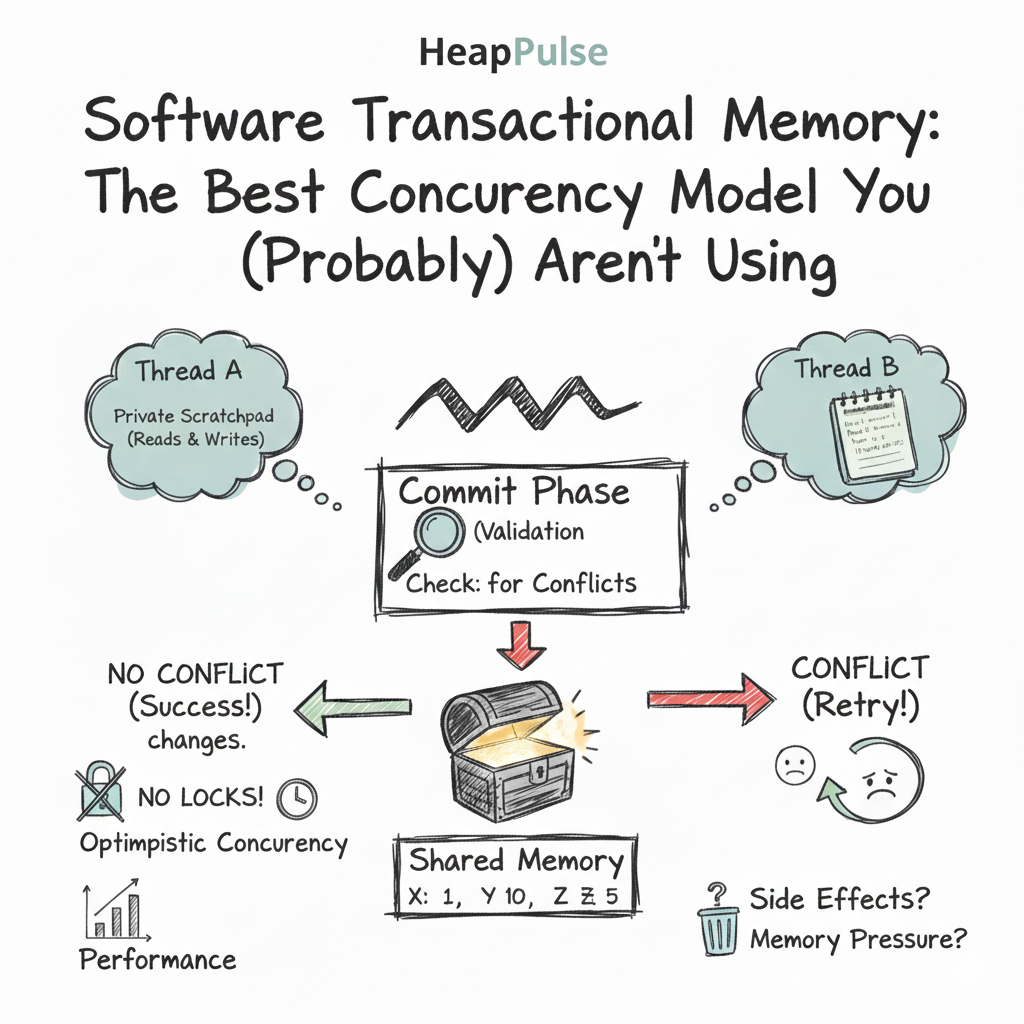

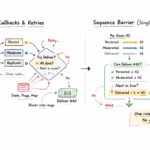

The secret behind STM is optimistic concurrency. It lets every thread run at full speed and only checks for conflicts at the end. So there’s no need for blocking other threads upfront, which can lead to better performance in scenarios with low contention.

Here is a simplified lifecycle of an STM transaction in a Java context, using libraries like Multiverse or Akka STM:

- The Private Notebook When a thread enters an atomic block, it does not touch the real shared memory immediately. Instead, it gets a private “scratchpad” or transaction log.

- Reads: When you read a variable, the system records the version you saw at that moment.

- Writes: When you update a variable, you write to your private scratchpad. The real data remains untouched.

- The Commit Phase (The Moment of Truth) When your code block finishes, the STM engine performs a validation check. It asks a simple question: “Has anyone changed the variables I read since I started?”

- If No: The engine atomically “flushes” your private writes to the real memory. The transaction succeeds, and all changes become visible instantly to other threads.

- If Yes: A conflict occurred. The system discards your scratchpad (rollback) and silently restarts the transaction from the beginning with fresh data.

This optimistic model minimizes waiting and maximizes parallel execution when conflicts are rare, which is common in many real-world Java applications. This becomes even more efficient in low-contention scenarios, allowing you to scale without the complexity of fine-grained locking.

Also, since there are no locks, you simply won’t have to worry about deadlocks or priority inversion.

A Practical Example: Atomic Inventory Management

Let us look at a common scenario: processing concurrent orders in an e-commerce system. We need to atomically decrement stock and increment a sales counter.

To ensure data consistency, it is obvious we need to maintain some locking mechanism. We could do this with standard Java locks. This works as long as we effectively manage lock ordering to avoid issues like deadlocks and race conditions.

However, with STM, we simply wrap the operations in an atomic block and treat them as a single unit. This ensures that if multiple threads try to update the stock and sales values at once, any conflict is detected automatically. The data remains consistent and the system retries the operation automatically using the newest available values.

Here is the implementation using the Multiverse library.

public class ProductInventory {

private final TxnInteger stockLevel;

private final TxnInteger totalSales;

public ProductInventory(int initialStock) {

// We initialize transactional references

this.stockLevel = StmUtils.newTxnInteger(initialStock);

this.totalSales = StmUtils.newTxnInteger(0);

}

public boolean tryProcessSale(int quantity) {

try {

StmUtils.atomic(() -> {

int current = stockLevel.get();

if (current < quantity) {

throw new IllegalStateException("Insufficient stock");

}

stockLevel.decrement(quantity);

totalSales.increment(quantity);

});

return true;

} catch (IllegalStateException e) {

return false; // Transaction aborted due to business logic

}

}

public int getStockLevel() {

return stockLevel.atomicGet();

}

public int getTotalSales() {

return totalSales.atomicGet();

}

}We can test this with a simple simulation:

public class OrderProcessingDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

ProductInventory inventory = new ProductInventory(50);

ExecutorService pool = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(20);

// Simulate 100 concurrent order attempts, each for 3 units

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

pool.submit(() -> {

if (inventory.tryProcessSale(3)) {

System.out.println("Order fulfilled. Stock left: " + inventory.getStockLevel());

} else {

System.out.println("Order rejected - out of stock");

}

});

}

pool.shutdown();

pool.awaitTermination(10, TimeUnit.SECONDS);

System.out.println("Final stock: " + inventory.getStockLevel());

System.out.println("Total units sold: " + inventory.getTotalSales());

}

}Why this is better than locking:

- Consistency is Guaranteed: It is impossible for the stock to go down without the sales going up. The

atomicblock ensures they happen together or not at all. - No Overselling: Even with 100 threads hammering the system, the

stockLevelwill never drop below zero. The STM engine detects conflicts and forces late arriving threads to retry or fail safely. - Extensibility: If you later want to add a third step, such as

reserveShippingSlot(), you just add it inside the atomic lambda. You do not need to re-architect your locking strategy.

Drawbacks of STM

If STM is so powerful, why isn’t it in every Java project? Like any tool, it comes with trade-offs that you must consider.

1. Performance Overhead Maintaining the “Private Notebook” is not free. The system must track every read and write to detect conflicts. In high-performance systems with massive data throughput, this bookkeeping can make STM significantly slower than raw, highly optimized locks.

2. The Side-Effect Problem You cannot perform I/O operations inside an atomic block. If you send an email or write to a file inside a transaction and that transaction retries five times, you will send five emails. You can only safely execute code that stays within the managed memory.

3. Memory Pressure Because every transaction creates a log of its changes before committing, STM can increase the pressure on the Java Garbage Collector. If your application creates thousands of transactions per second, you may see more frequent GC pauses.

Conclusion

Software Transactional Memory is not a replacement for every lock in your codebase. However, for complex state management where correctness is non-negotiable, it is a game changer. It moves the burden of concurrency from the developer to the system, letting you focus on the logic instead of issues like race conditions and deadlocks.