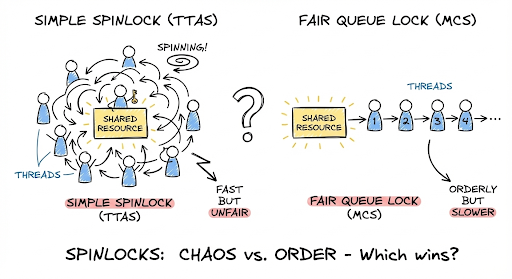

In our previous post, we discussed some advanced spinlock mechanisms in Java. We explored the advantages and drawbacks of popular spinning mechanisms, from the simple Test-And-Set (TAS) and cache-aware Test-Test-And-Set (TTAS), to fairness-oriented Ticket locks, and finally the scalable queue-based solutions like MCS and CLH.

In this post, we will implement the MCS Lock and run a benchmark against TTAS, ReentrantLock, and the intrinsic synchronized block to see how they perform under real contention.

Implementing the MCS Lock in Java

To implement the MCS lock, its important to read the paper by John M. Mellor-Crummey and Michael L. Scott, “Algorithms for scalable synchronization on shared-memory multiprocessors.“ Here we implement a simple version.

The MCS lock uses a linked list of waiting threads. To implement this efficiently in Java, we need two things:

- A QNode: A record representing a waiting thread.

- A Tail Pointer: An atomic reference to the last thread in the queue.

To ensure minimum overhead, we avoid creating full AtomicReference objects for every node. Instead, we use AtomicReferenceFieldUpdater to perform atomic operations directly on volatile fields.

Here is the complete implementation:

import java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicReferenceFieldUpdater;

class MCSLock {

private static class QNode {

volatile QNode next;

volatile boolean locked;

QNode() {

next = null;

locked = true;

}

}

private volatile QNode tail;

private static final AtomicReferenceFieldUpdater<MCSLock, QNode>

TAIL_UPDATER = AtomicReferenceFieldUpdater.newUpdater(

MCSLock.class, QNode.class, "tail");

private final ThreadLocal<QNode> myNode = ThreadLocal.withInitial(QNode::new);

public void acquire() {

QNode current = myNode.get();

current.next = null;

QNode predecessor = TAIL_UPDATER.getAndSet(this, current);

if (predecessor != null) {

current.locked = true;

predecessor.next = current;

while (current.locked) {

Thread.onSpinWait();

}

}

}

public void release() {

QNode current = myNode.get();

if (current.next == null) {

if (TAIL_UPDATER.compareAndSet(this, current, null)) {

return;

}

while (current.next == null) {

Thread.onSpinWait();

}

}

current.next.locked = false;

current.next = null;

}

}JMH Benchmark

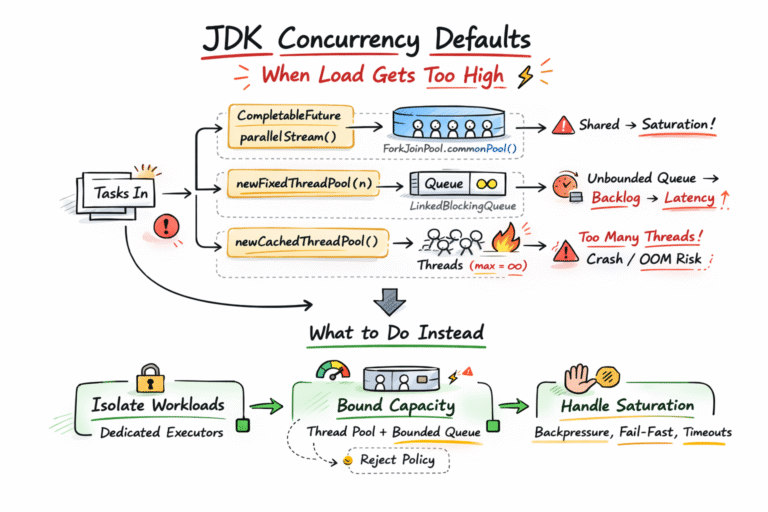

We used JMH (Java Microbenchmark Harness) to test four locks: TTASLock, MCSLock, ReentrantLock, and Synchronized.

The tests were executed on an Intel i7-1165G7 (Tiger Lake) equipped with 4 Cores and 8 Threads. We forced oversubscription by running 32 threads on the 8 available logical cores.

The performance is evaluated across three distinct scenarios to capture the full behavior of the locks:

- Raw Overhead (0 Work): Measuring the intrinsic cost of the lock mechanism itself with an empty critical section.

- Medium Contention (50 Work Tokens): Simulating a standard use case where threads hold the lock briefly, causing frequent contention.

- Heavy Workload (200 Work Tokens): Simulating long critical sections where execution time is dominated by the work rather than the lock.

Here is the code for the benchmark:

@State(Scope.Benchmark)

@BenchmarkMode(Mode.Throughput)

@OutputTimeUnit(TimeUnit.MICROSECONDS)

@Warmup(iterations = 5, time = 1)

@Measurement(iterations = 5, time = 1)

@Fork(3)

public class LockBenchmark {

// --- Configurations ---

// We vary the number of threads to see the scalability curve.

@Param({ "8", "16", "32" })

public int threads;

// We vary the "work" done inside the lock.

// 0 = Benchmark 1 (Raw overhead)

// 50 = Benchmark 2 (Simulated work)

@Param({ "0", "50", "200" })

public int workTokens;

private long sharedCounter = 0;

// 1. Standard ReentrantLock

private final Lock reentrantLock = new ReentrantLock();

// 2. Intrinsic Lock Object (for synchronized)

private final Object syncLock = new Object();

// 3. Custom TTAS Lock

private final TTASLock ttasLock = new TTASLock();

// 4. Custom MCS Lock

private final MCSLock mcsLock = new MCSLock();

// --- Benchmarks ---

@Benchmark

public void testSynchronized(Blackhole bh) {

synchronized (syncLock) {

criticalSection(bh);

}

}

@Benchmark

public void testReentrantLock(Blackhole bh) {

reentrantLock.lock();

try {

criticalSection(bh);

} finally {

reentrantLock.unlock();

}

}

@Benchmark

public void testTTASLock(Blackhole bh) {

ttasLock.lock();

try {

criticalSection(bh);

} finally {

ttasLock.unlock();

}

}

@Benchmark

public void testMCSLock(Blackhole bh) {

mcsLock.acquire();

try {

criticalSection(bh);

} finally {

mcsLock.release();

}

}

// --- Helper ---

/**

* The Critical Section.

* If workTokens == 0, it's just a variable increment.

* If workTokens > 0, we burn CPU cycles.

*/

private void criticalSection(Blackhole bh) {

if (workTokens > 0) {

Blackhole.consumeCPU(workTokens);

}

sharedCounter++;

bh.consume(sharedCounter);

}

}Results

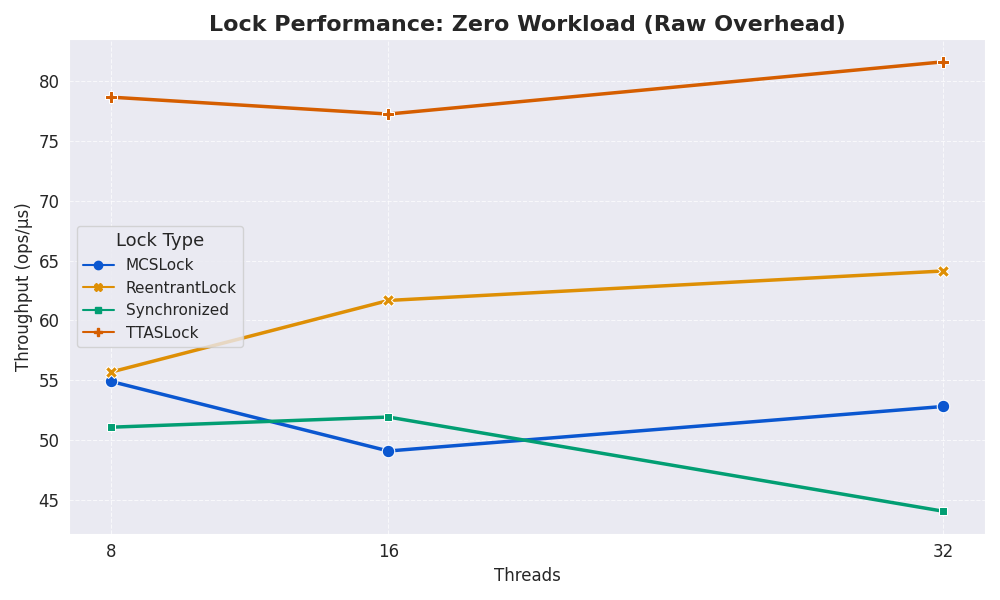

Scenario 1: Raw Lock Overhead (Work = 0)

In the first case with little or no work done, the major overhead is the lock acquisition mechanism itself.

Here we see that TTASLock is the fastest because it executes the fewest CPU instructions. MCS and synchronized are slower because MCS adds overhead from managing its queue nodes, while synchronized has extra overhead from JVM monitor management. ReentrantLock remains competitive by using fast hardware CAS instructions.

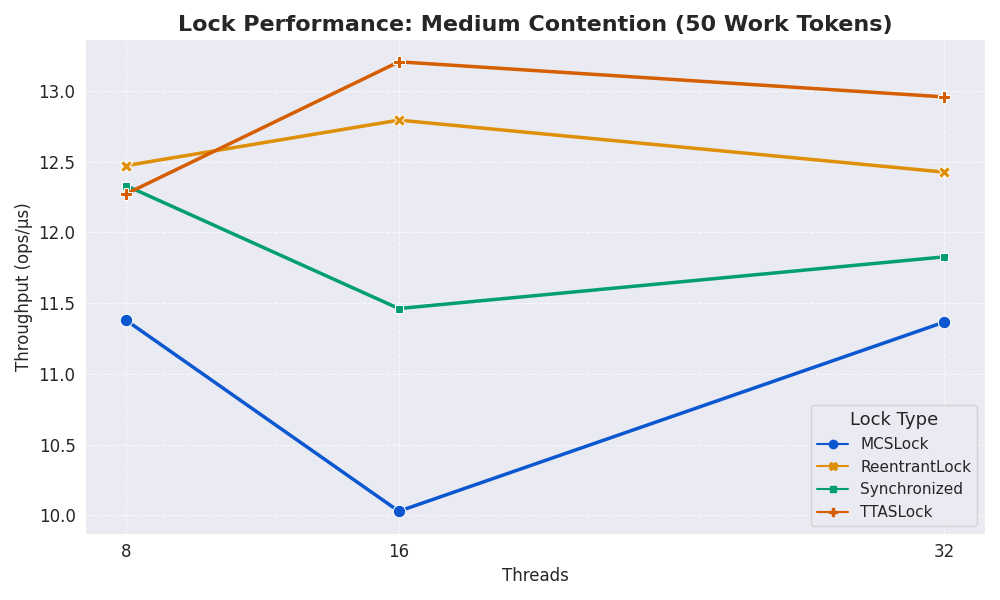

Scenario 2: Medium Contention (Work = 50)

In this case, we add more work inside the lock, so the main bottleneck shifts from the raw cost of acquiring the lock to the overhead caused by moving lock ownership between cores.

MCSLock performs worst here because it enforces strict FIFO fairness. The lock must transfer ownership to the next waiting core, causing costly cache misses and bus traffic. TTAS and ReentrantLock perform better because they allow a thread on the current core to reacquire the lock immediately, keeping the lock’s state in the local cache and avoiding expensive transfers.

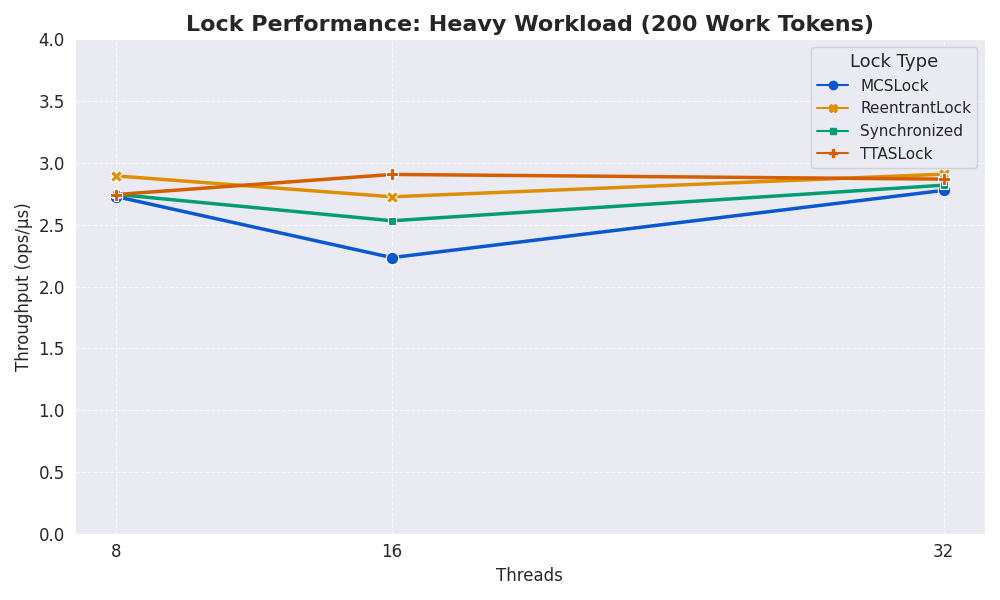

Scenario 3: Heavy Workload (Work = 200)

In this case, we add significantly more work (200 tokens) inside the lock. The main bottleneck is no longer acquiring the lock but the CPU’s ability to execute the work itself.

All four locks perform almost identically. When the work inside the critical section is much larger than the lock overhead, performance is limited by the work, not the lock. The choice of lock becomes irrelevant, and any differences are negligible.

Conclusion

From our benchmark results, it is obvious that lock performance is dependent on the workload context. In most Java applications, ReentrantLock(unfair) or synchronized is the best choice because they are efficient, stable, and handle thread parking well. TTAS Lock is fast in raw throughput but can suffer from thread starvation.

MCSLock performs worst under medium contention because it enforces strict FIFO fairness. However, it is extremely useful in multiprocessor systems with high contention, as it avoids excessive CPU spinning and provides predictable lock handoff.

Locks that combine spinning and parking, such as ReentrantLock, offer a practical middle ground. They spin briefly while checking if the lock is available and, if it is still held, park the thread to avoid wasting CPU cycles.